Writer, curator, and educator Ariel Goldberg has created a collage in response to the invitation to participate in the folio dedicated to the visual artist Fran Herndon. During the 1960’s, Herndon developed a collage practice with two main series: the Sports Collages and the Antiwar Collages. In the former, Herndon channeled questions of race by collaging photographs from Sports Illustrated magazine — a context in which these issues were not explicitly addressed, yet which included images of famous non-white athletes that Herndon recontextualized into other visual and conceptual structures. In her antiwar collages, Herndon sourced black-and-white and color images marked by a strong military presence.

If these collages reflect a deep attunement to the unfolding of events around the artist, Ariel Goldberg’s collage instead places pressure on the technologies of capture themselves. Goldberg saturates their collage with photographic cameras and gadgets sourced from the British magazine Amateur Photographer from 1989, insisting not only on where professional photographers point their cameras and what they put into circulation, but also on how we all participate in constructing a “visual common sense” — by reinforcing the repetition of certain types of images and framings while discouraging others.

What follows is an informal conversation between Ariel Goldberg and Juf (Bea Ortega Botas and Leto Ybarra) discussing Goldberg’s collage and Herndon’s work.

Ariel Goldberg: I made this collage while reading and contemplating the essays and books on Fran Herndon that you have compiled and shared with me. At the same time, I was reorganizing my clutter piles in my studio, and it occurred to me, instead of drafting remarks about photography as source material for Herndon’s visual language, I might experiment with making a collage with Herndon on my mind. I began cutting words and objects out of this one magazine that I got in 2014, one day I was wandering through the used bookstores in El Centro in Mexico City. I was there doing the SOMA Summer artist residency/seminar. Having a weakness for old photo things, I bought several magazines and hung on to them for ten years.

JUF: It is funny that you bought those magazines in Mexico. Fran and her husband spent some time there in 1961, and we randomly found out about that trip that they made when we visited Bancroft Library in San Francisco a few months ago. They have a couple of postcards that Fran sent to Jack Spicer from Mexico, sharing details about what seemed like a life changing trip. There always seems to be these magical connections between these two figures… But let’s get back to Fran and your collage. Were you thinking specifically about her Sports collages when you made this work?

AG: Yes, the Sports and Antiwar collages—and I love the synchronicites. I think I was drawn to working with a mass-market print magazine to echo Herndon’s choice to work with Sports Illustrated. Material from mainstream, consumer-based culture. The magazine I ended up using for my collage, Amateur Photographer was marketed to hobbyists and commercial photographers alike so it was distinct from fine art photography. Amateur Photographer is comprised of product reviews that blur with photo retailer ads courting buyers. Meanwhile Herndon looking at the narratives and images assembled for readers of a sports magazine, or I imagine news magazines like LIFE—widely available periodicals—to question the absurd logics that uphold subjugation in representations of patriotism, gender roles, anti-blackness, and U.S. empire.

JUF: In previous creative work you have already dealt with found materials from mass consumed media. Can you tell us a little bit more about this gesture of re-directing or subtracting something from its original milieu and function, especially with regards to a long genealogy and history of minoritized practitioners that have previously used collage for instance.

AG: I was very much inspired to study poetry because it is an agile and affordable medium to talk back to various unspoken biases in how current events are framed. I came to Fran Herndon’s Bay Area, in the mid-aughts and found a culture that directly addressed U.S. forever wars and the institutions that normalized the horrors of the U.S. military. Poets supported artists, artists supported poets—this was different then the more narrow and individualistic ideas of being an artist I had seen modeled in NYC, although now I understand all places have these networks of artists literally telling their friends, you are an artist, make art, tell me about it, let’s make art together. When I went to the orientation for an MFA program at Mills in Creative Writing, Juliana Spahr showed a pie chart of how a poetry community sustains itself and how she encourages newcomers to enter with a curious spirit: what can I do to volunteer time, resources, etc., to keep poetry moving and responding?

My first chapbook Picture Cameras (2010, NoNo Press) reflected this practical ethos. Poet and book artist Lara Durback supported my idea to make a book with letter pressed poetry on found materials—We used the randomness yet perfectness of stacks of Shutterbug photo magazine that I found at Urban Ore, a giant Bay Area thrift store. Shutterbug was like the 1989 Amateur Photographer magazine. My poems on top of these pages were about photography and war, interdependent industries. Looking back at this now, the consumer photography magazines eerily avoid the cataclysmic year in terms of many historical events unfolding. When I think of 1989, I think of government negligence around public health and HIV/AIDS. The fall of the Berlin Wall, Tiananmen Square, and the decades long international, economic pressure to end Apartheid in South Africa mounting. None of that social and political context appears in the pages of a magazine like Shutterbug or Amateur Photographer. There is no acknowledgement of racism, sexism, disposability of queer people, of drug users, of black and brown communities experiencing the war on drugs and mass incarceration, and yet all of that is happening at exactly the same time as selling camera equipment of every imaginable variety.

JUF: Pointing to these absences and silences on the magazine is a brilliant way to think about the absolute harshness and capitulating feeling that comes when one realizes that the world, the everydayness, keeps going on, keeps happening, regardless of genocides, deaths, and continuous violences. This image of someone reading a magazine, with a cup of coffee in their hand, skimming through the pages, whilst the world is collapsing is really powerful. And we guess Herndon’s Sports collages can be thought of in a similar way. The way she takes this mass consumed magazine, that arrives smoothly at your mail and is produced for a “light-leisure-like reading,” and injects in them urgent racial and political issues.

AG: Absolutely! Herndon voices what the editors of the leisure magazines strenuously keep unspoken. I think of Herndon’s collage King Football, which I think depicts a skull shrouded in military gear composed of clipped footage of football players and bodies in combat, one clipped headline, “The Day of Devastation” suggests a macabre absence to the all-American sport. I wanted to time travel, stay in the devastation, working exclusively with found language and materials. Relieved from the burden of coming up with the words, I just needed to focus on selection and arrangement drawn from clipping this one 1989 photography magazine. Photography is always wrestling with the things it can do to conjure memories or repressed histories, but it also collects and documents, like everything that is horrific in society as well.

JUF: Let’s get back to your collage, let’s have a closer look…

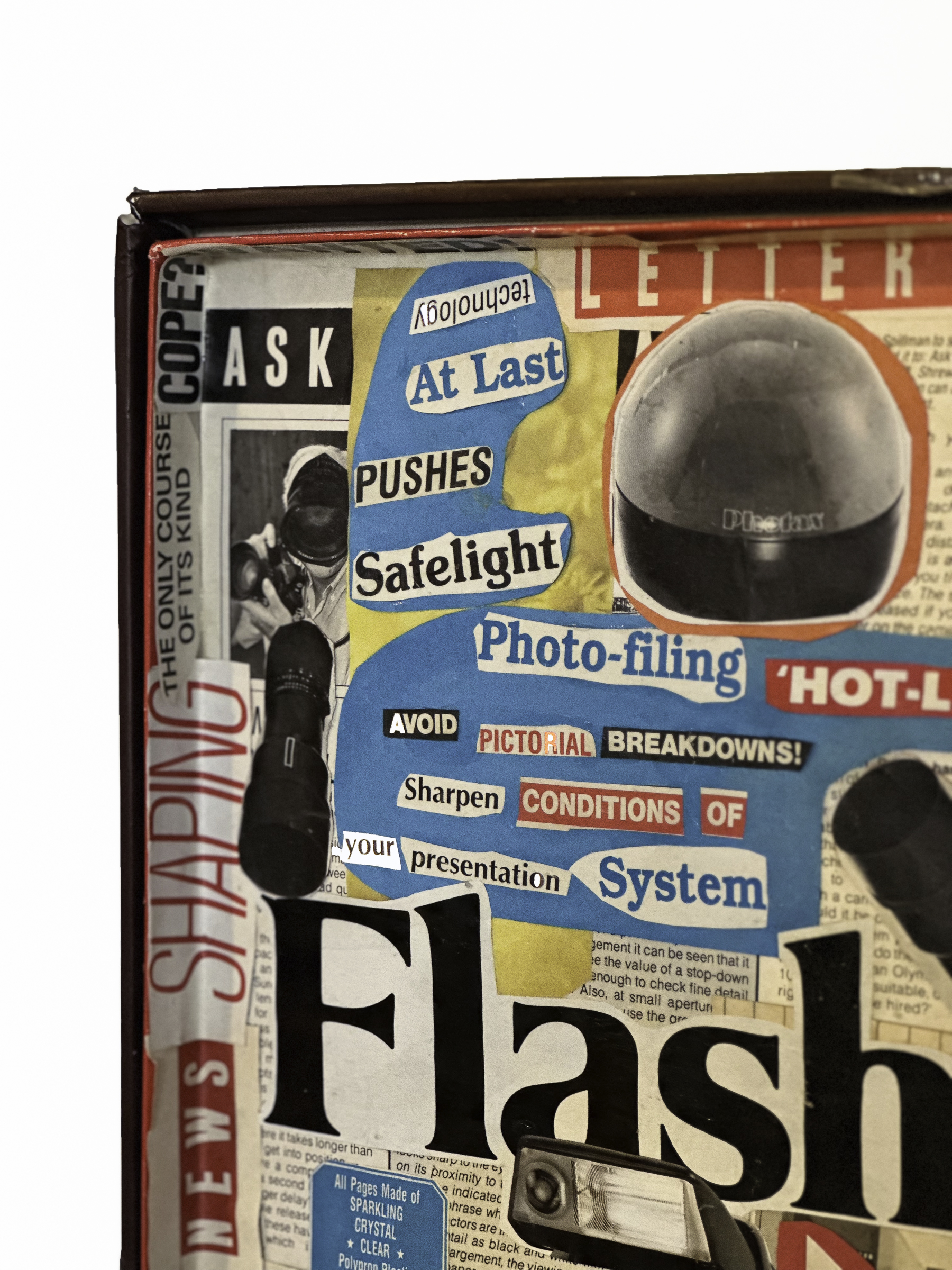

AG: I was looking for a cardboard surface to do the collage on inside my storage of art and ephemera in this one room of my apartment that we're sitting in. I found a mismatching 16 by 20 inch black and white paper photo box. The bottom side is labeled Agfa, a brand that manufactured black and white darkroom paper and developing chemicals. The top of the box is Ilford, a popular brand that competed with Agfa. Both box halves once held high quality, multi grade, warm tone, light sensitive black and white papers that were advertised within Amateur Photography. In the collage there's a little bit of a play on outdated photography materials, because people are very rarely working in dark room photography or analog photography these days. We are traveling to a predigital era.

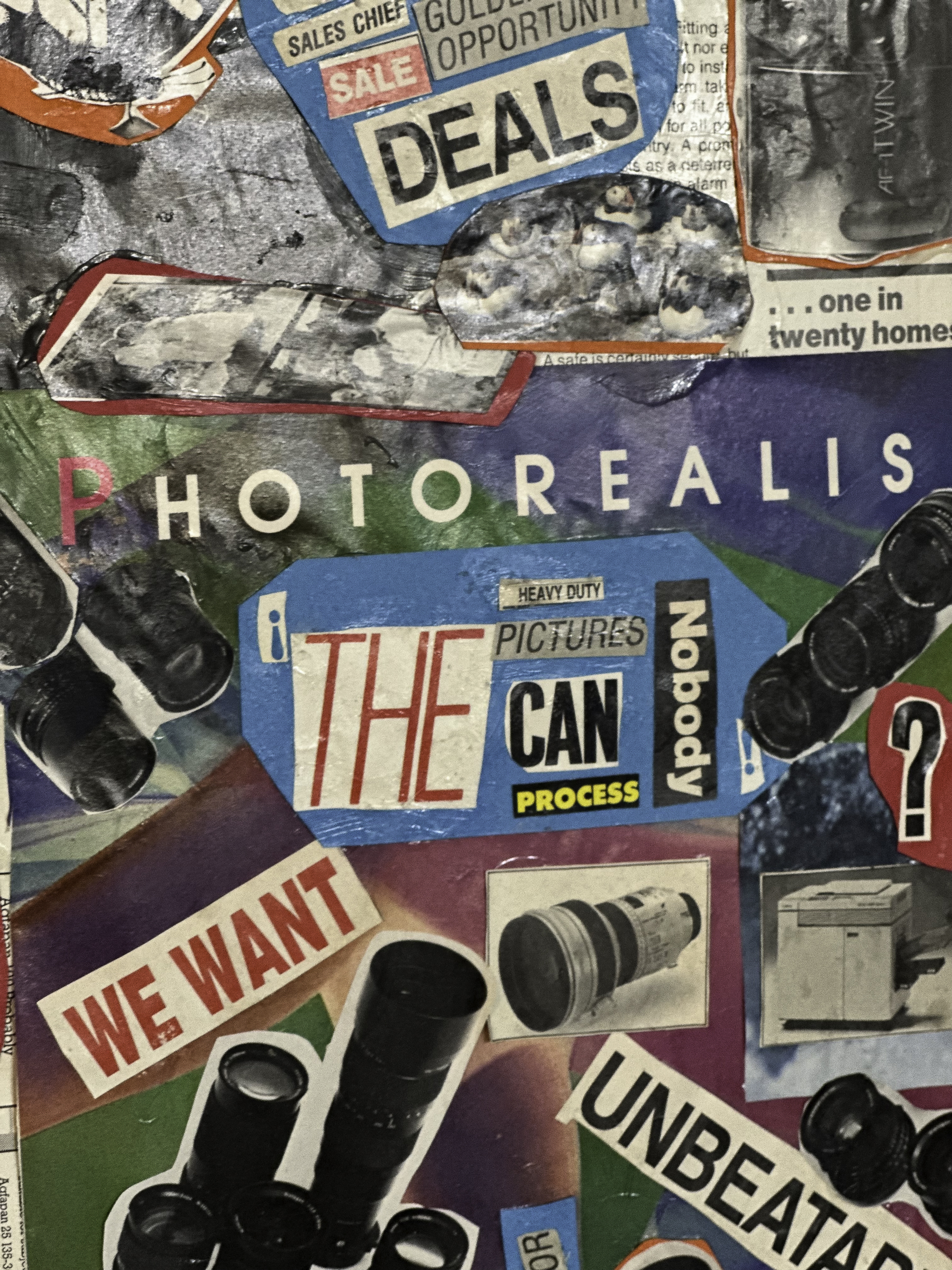

There are about four-six sections of the collage overall. It is a very maximalist approach. I decided there wouldn't be any visible raw substrate or blank background. I layered excerpts from the photo magazine to create a sort of loud, Times Square busy-ness to the tools of photography. I tried to follow an intuitive process of cutting out objects and descriptors. You can find lenses, a slide projector, photo albums, point and shoot cameras, single lens reflex cameras, tripods, monopods, negative holders, paper, film, chemicals for processing, camera bags, a safe light for the dark room--oh, and there's a Xerox machine! The slide projector is in the middle of the collage because I have a special attachment to slides and slide projectors. Some of the stuff is basic analog kit and others idiosyncratic, but it's all mostly junk now. I don’t know why I am so drawn to preserving the obsolete tools of image-making, perhaps I think I’ll understand the history and practice of the medium with this accumulation.

JUF: What about the language? The words that you include in the collage? This is something that Herndon also did in her collages. Where words with a particular heaviness were cut out of headlines and included amongst the sport figures –such as “Great Collapse,” “A question of violence,” or “the day of devastation.” She obviously had a strong interest in language and a direct connection with poetry.

AG: In my collage I concocted the line, “the heavy-duty pictures nobody can process.” It’s not as explicit as Herndon gets, but I am preoccupied with the normalization of mass death. The ongoing Israeli-US backed genocide in Palestine, which is often referred to as the first live-streamed genocide. I was trying to create a narrative with the language about consumerism, capitalism enabled by technological equipment… All of these apparatuses that, at the end of the day, are used to take a photo of, like, cute ducks or a sunset or people in your life while also being manufactured by militaries and states. I'll just read some texts from the collage: “Electronics / Glamor …” / “Ask…action…the second hand…you tell us…urgent…weatherproof”/ “The only course of its kind!” I was reading a band of words that's sort of like the stream of text on LED signs in Times Square. Disjointed, list-like headlines.

Like I mentioned, the quadrants of the collage have different themes, and are nestled like little poems. For example: “technology at last pushes safe light”, “photo-filing, hot-line, avoid pictorial breakdowns!”, “sharpen conditions of your presentation system.” “Flash.” That’s a sample of some language in my collage. Little clusters bounce around, like empty promises: “beat the thief”, “89 deals…golden opportunity.” The middle right quadrant retains a full-page color ad—“Photorealism—for Kodak Ektar 25, which was a slide film on the market boasting vivid sharp color. Color slide film is luscious compared to print film, and as a positive could be projected, cinematically at home, using a slide projector.

JUF: Yeah, it’s like net fishing for us. It brings to the surface everything, what you expected, what you couldn’t see, what you didn’t even imagine and even less want to see or keep…

AG: Perhaps my collage pokes at the supposed innocence of photography as it's presented like a hobbyist gadget, so photo enthusiasts will buy all these toys to see the world in still images—to what end? Cutting up the ads and editorial copy I came up with the phrase “image confusion” which feels relevant to the double bind of photography. I was trying not to take it too seriously and assemble my affinities for the relative slowness of working with light sensitive film, processing, enlarging prints, editing from a roll as opposed to thousands of images on one’s mobile phone.

JUF: We love the saturation and accumulation of objects and gadgets in your work. We don’t think that is exactly the strategy that Fran followed. Her collages do include various images, with different tones, scales, temporalities etc. but I think she measured a lot how many of them to include and instead of wanting to cover all of the surface I think she sort of wanted the surface to be quite present and vibrant and visible with different forms and colours. In fact, several of the images she included in turn became abstract surfaces onto which other images were superimposed.

We also like that your collage is focused on the other side of that which is represented, in the equipment that captures but isn’t captured and that enables the subsequent circulation of those images. There is this small poem that you create in the collage that for us speaks directly about this – “The heavy duty pictures nobody can process”-- and to the fact you mentioned earlier about making this collage with the ongoing genocide in mind. But we think that it can also be applied to Herndon’s time. Especially in relation to the antiwar collages that she did during the Vietnam war.

AG: With Fran, if I can call her that--I share a desire to be direct and anti-war in my work so as to join those resisting western colonialism broadly. What is up with greed and death still ruling the day? Whether within a 1960’s Sports Illustrated magazine or a 1980’s Amateur Photographer, I think the editors address an imagined reader, who is a cisgender man into athletes or military displays of destruction. Meanwhile, on these pages, women play the role of exemplars of beauty, sex, wife, spectator—those who selflessly prop up men’s exceptional prowess. As an aside, the classified sections of these consumer photography magazines also advertised sex, not so discreetly embedded within the presumption of needing models to pose for pictures. There were ads for escorts and even long-term arrangements. I didn’t include such ads in my collage. This is the culture of sexism that Herndon lived through and defied, but it’s also the culture that led to this delay in her work being known compared to cis-gender male peers.

JUF: Now that you mention Fran and her relation to a wider circle of white cis-gender male peers such as Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, Jess or Robin Blaser, we can maybe wrap up by discussing this particular environment in the Bay Area. We remember that you knew Norma Cole — who was also a close friend of Herndon — and that it would surprise you not to have known about Herndon given your familiarity with many of her friends, but then again that’s how history, and the possibility of “success,” and visibility and inequalities all show up.

AG: I moved to the Bay Area in 2007 and I was there until 2011; four very formative years for me. I think I must have been at a reading or art event with Herndon, but we never met. I nervously attended a Christmas Eve party once at Kevin Killian and Dodie Bellamy’s apartment where Herndon’s art was likely on the walls. Syd Staiti introduced Jack Spicer to me—who I understood as a tragic gay poet hero whose biography is on my shelf. You’ve reminded me, Norma Cole is another connection. As I mentioned, I went to graduate school at Mills College, which no longer exists, and I met a lot of incredible poets and teachers. I was lucky to take classes with Juliana Spahr, Susan Gevirtz, Leslie Scalepino, Truong Tran, Stephen Ratcliffe, and Dodie. I was amazed at how strong and developed the literary culture was in the Bay Area. In New York City, I had been to The Poetry Project, but it's just a bigger city, so it's harder to find that intimate feeling that I was fortunate to find in the Bay Area. Something devotional and constant that I think connected me to Fran Herndon even if I didn’t know it at the time. I am reflecting on this because my partner has brought me back to the Bay Area as they do a PhD out here.

The work you're doing with Fran Herndon, to create an inventory and access to her work, reminds me of the Bay Area’s culture of small press publishing, house readings, low-cost or free workshops, all the necessary support structures for writers and artists. It reminds me of the artists that had day jobs. Presenting their art was embedded within their ways of making money, building families, friendships and social worlds around art.