A selection of letters from Even Strange Ghosts Can Be Shared: The Collected Letters of Jack Spicer

The letters of poet Jack Spicer (1925-1965) are a vital component of his unique oeuvre; they radiate with the brilliance, ferocity, and vulnerability that characterizes his poetry. In fall 2025 — the year of Spicer’s centenary — Wesleyan University Press will publish Even Strange Ghosts Can Be Shared: The Collected Letters of Jack Spicer, edited by Kevin Killian, Kelly Holt, and Daniel Benjamin. The over 300 fully annotated letters in this volume contribute vital details to Spicer’s biography, and stand alongside Spicer’s previously published works as key components of his inventive and influential writings.

This selection of letters begins in 1954 during Spicer’s tenure working as a professor at California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco, writing to his former student Graham Mackintosh (1935–2015). Spicer writes about his involvement with the 6 Gallery, which Spicer founded with five of his students at CSFA. Hosting both poetry readings and art openings, the 6 Gallery was later the location of Allen Ginsberg’s first performance of “Howl.” Later letters touch on Spicer’s continued integration of the visual art and literary scenes in San Francisco. They include adoring appreciations as well as the “tempests in pisspots” which sometimes characterized Spicer’s interactions with his collaborators.

— Daniel Benjamin

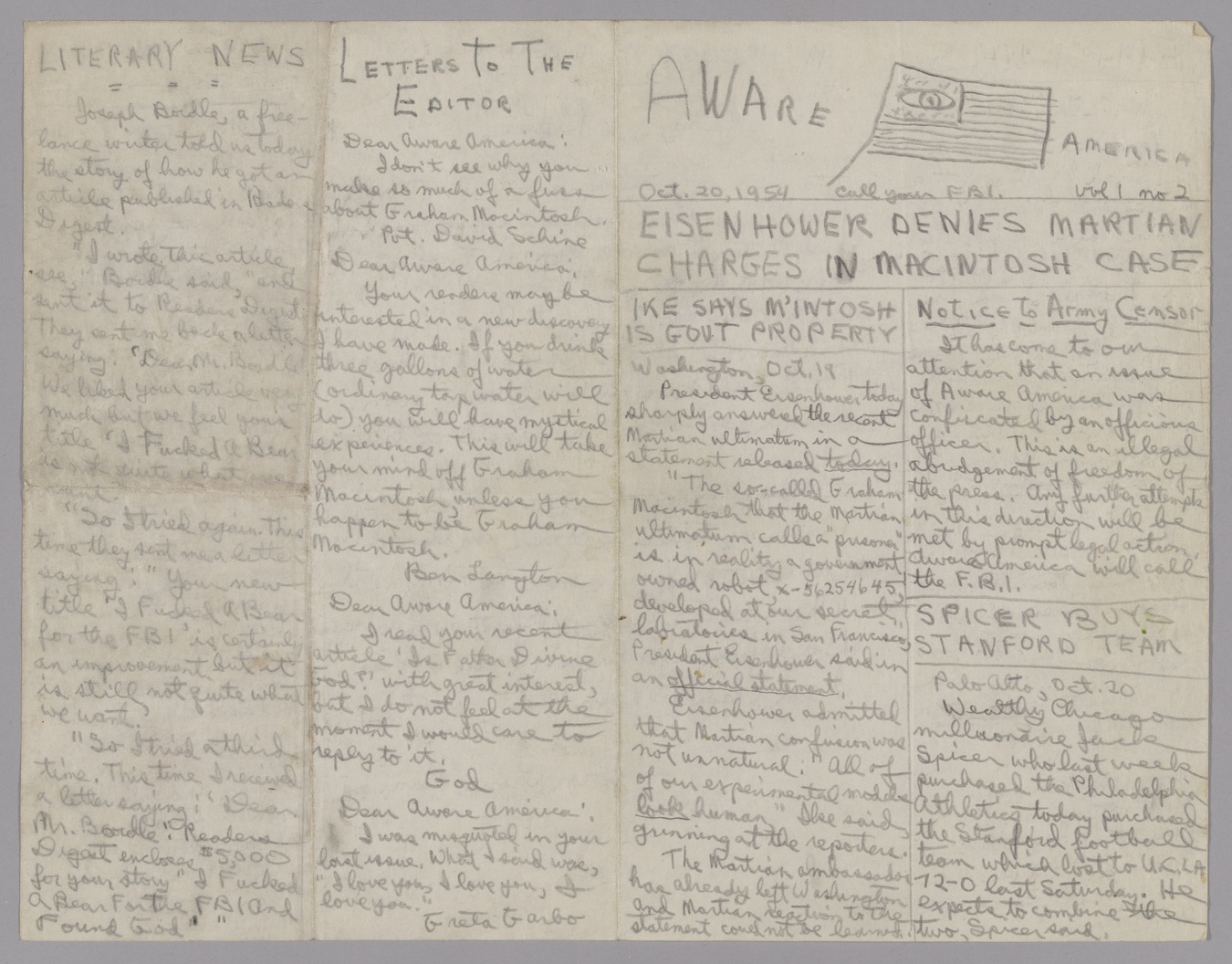

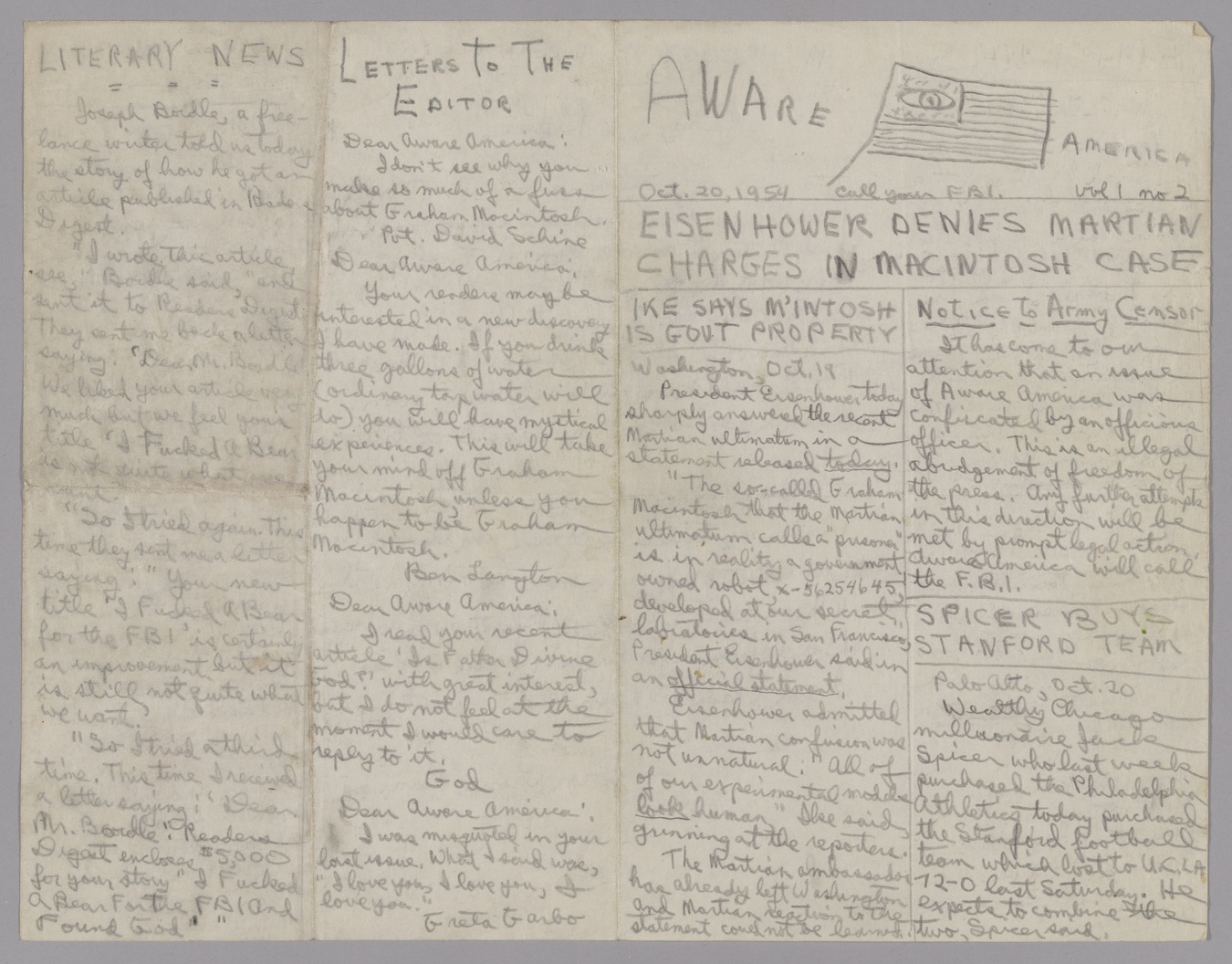

To Graham Mackintosh #7

Wednesday, October 27, 1954

{975 Sutter Street, Apartment C, San Francisco, Calif.}

Dear Mac,

No Aware America today. The pre-opening of the 6 at the Opus One is over and I’m sick at heart. We made money (fifty bucks) but the whole thing was an unqualified artistic failure. The poetry tapes (the one you heard at the festival and a new one we made) had sounded pretty good over ordinary equipment. Over the super hi-fi rigs at the Opus One the instruments drowned out the voice and made batlike squeaks. Wally improvised on the light machine to an experimental music (?) tape of Sandy Jacob’s which tested what could be done to the human ear other than pouring boiling oil into it. It was perhaps a blessing that only the same old tired faces came that you usually see at something like this. I don’t mind offending them.

Anyway all the magic that was generated by the Art Festival booth is dissipated and I feel like someone in a ragged Halloween costume at 6:30 the next morning. I wish you were here to cheer me up, but then I wish I were there to cheer you up.

Yours

Jack

“Jack Spicer Papers,” BANC MSS 71/135, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. “Aware America” was a newsletter that Spicer produced for Mackintosh modeled on Cold War anti-Communist propaganda. John Allen Ryan (1928–1994), one of the members of the 6 Gallery, remembers of the “pre-opening” event: “We had another fund raising party at the Opus One, a club run by Wynn Astin in the basement of the Sentinel Building on Columbus where the hungry i club began. Wally Bill [Hedrick] & I operated (or played, actually) a souped-up version of Hedrick’s light organ, an instrument-machine he’d been working on for many years, accompanied by jazz & other improvisational music. A lot of people came out for this, and it was a big success. We raised $30 or $40.” “The ‘6’ Gallery: Roots and Branches,” in The Beat Generation Galleries and Beyond (John Natsoulas Gallery, 1996), 59. Wally Bill Hedrick (1928–2003), Spicer’s student at the California School of Fine Arts, was one of the co-founders of the 6 Gallery. Henry Sandy Jacobs (1925–2015), the electronic musician and sound artist, had only moved to Berkeley from Chicago the year before, bringing with him a reputation as a daring experimentalist in reel-to-reel tape recordings he manipulated to include ambient sounds, street noise, and musique concrète. In 1955 Folkways Records would release his first LP of these sounds, Radio Programme #1: Music and Folklore, which includes the “Sonata for Loudspeaker” played at Opus One. The question mark in Spicer’s sentence after the term “experimental music” is his own, suggesting some skepticism. Of the earlier Art Festival booth, John Allen Ryan recalled: “We rented a booth at the San Francisco Art Festival in Aquatic Park, in order to raise money for the new venture. It was, as Herb Caen reported in the San Francisco Sunday Examiner on September 26, 1954, ‘sponsored by six people interested in art, music, poetry, integrity and other worthwhile things.’ Spicer played a reel-to-reel tape of his ‘California Poems’ continuously for all three days, irritating many nearby who did not ‘dig’ our idea of a ‘total art performance.’ A lot of the people in the booths around us were furious, but it was a great deal of fun” (“The ‘6’ Gallery: Roots and Branches,” 59).

To Graham Mackintosh #30

Monday, December 13, 1954

{975 Sutter Street, Apartment C, San Francisco, Calif.}

Dear Mac,

On the day after I’ve seen you it always seems that I could write a letter to you that could go on forever. Your image is restored to me. What, after three weeks of absence had become a shadowy Graham, a Graham not very far removed from my merely talking to myself, has become a real Graham, a Graham made of flesh and tears. But not completely—the Graham I played chess with yesterday is not the Graham I can play chess with at any time I choose, he was a temporary Graham, realer than the shadowy Graham that I play chess with every day in my imagination, but not as real as the Graham I hope for—the Graham unrestricted by time.

There were so many things I couldn’t get to say to you (for, of course, I was only the half-real Jack—the Jack who is only a little better than a letter), things about hope and courage. This overtime period is extremely important (you lost the last game in an overtime period, remember, by the closest of margins), but when I tried to give you words of hope and courage they would stick in my throat—I guess because, in the last analysis, we can’t give hope and courage to another person—only those things which hope and courage are based on.

After you left, someone gave me a kaleidoscope too. It will give us a sort of a new connection—when I look into it, I can imagine that you may be looking into yours and that we may be seeing the same pattern. Of course the army, which hates kaleidoscopes because their patterns cannot possibly have numbers, will probably confiscate yours, but, if they don’t, we may be able to work out some method of communication with them—looking into them at the same time and your pattern answering mine or something like that. Kaleidoscopes are also good for telling fortunes—ask it a question and look into the tube, then it becomes just a question of interpretation.

This letter has been the most painful to write of any (I guess you became realer to me this leave) and I can hardly wait until you start becoming unreal again and I don’t feel the pain of your pain. Yet the pain is worth it and curiously mixed with pleasure and I have the curious feeling that the permanent Graham and the permanent Jack will be playing chess together sooner than either of them realize.

Yours

Jack

“Jack Spicer Papers,” BANC MSS 71/135, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

To Russell FitzGerald #2

{1958}

Dear Russ,

Just a note (which I hope you throw away or keep but don’t send back as I don’t see how sending back negates a human utterance) about why I am bugged about the Elegies.

At least five decent painters (to be honest about it, make it four) have asked me to let them do illustrations for them—three of them long before White Rabbit existed. You presented me with a fait demi accompli in conversation and I was enthusiastic because I would (generally) trust your judgement on the relation between the graphic arts and poetry and because I believe you will be a great painter. This I tell you even in anger.

If this was to be a gift, it was shoddy to show it to people as a publishing project—(or even to show it to people before it was given). If it was to be a publishing project, at least you should have let me see and approve it (as a professional not your ex-roommate) before you let anyone see it. You and I are professionals (God knows) even before we are people. These are responsibilities. I do not wish my professional life to be exploited by my personal life and I’m sure you don’t wish yours to be either.

I’ll be very interested to see the manuscript and will give it to Joe for printing if I think it works for the poems. That is hardly a gift.

Jess Collins asked to illustrate Billy the Kid and I refused because I wanted you to do it. As a professional . . .

If you think I’ve taken advantage of a silly mistake of yours to bug you, you’re goddamn right. And so wrong.

Jack

“Jack Spicer Papers,” BANC MSS 2004/209, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, notebook draft. Russell FitzGerald (1932–1978), a painter trained at the Philadelphia Museum School of Art, moved to North Beach in 1957 and soon picked up Spicer during the Howl trial both attended. The two men moved in together and enjoyed a passionate relationship which became fractious quickly when FitzGerald developed a crush on the Beat poet Bob Kaufman and, after a pursuit of several months, seduced him and broke Spicer’s heart. The painter Jess Collins (1923-2004), who later went by only the name Jess, was the longtime partner of Spicer’s close friend Robert Duncan. He ultimately did illustrate Billy the Kid, which appeared in 1959 from Duncan’s Enkidu Surrogate.

To Alfred Frankenstein

{1959}

Dear Mr. Frankenstein:

Tom Albright tells me that he has left his position with you. I wonder if it might be possible for you to consider me as a replacement.

I have met you several times—both when I was an Instructor at the California School of Fine Arts and when I was one of the co-founders and publicity director in the early days of the 6 Gallery. My poetry and prose have been published in a number of little magazines including the San Francisco Scene issue of Evergreen Review. I feel confident that I should do an adequate job of reviewing painting and music and a more than adequate job of reviewing the somewhat confusing mixtures of these arts with poetry, which are now so popular.

If you are at all interested, I should be glad to talk to you at your convenience.

Sincerely Yours

“Jack Spicer Papers,” BANC MSS 2004/209, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, notebook draft. Alfred Frankenstein (1906–1981) was the music critic for the Chronicle beginning in 1934, and became their art critic too shortly afterward. He continued as art critic until 1979, resigning to become curator of American art at the M. H. de Young Museum in San Francisco. The critic Thomas Albright (1935–1984) left his position with Frankenstein in 1959 after being “caught up in the Beat movement,” according to his obituary. He returned to the Chronicle as art critic in the late 1960s, and wrote the definitive Art in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945–80: An Illustrated History (University of California Press, 1985).

To Donald Allen #10

{1959}

{214 Sunnyside St., Piedmont, Calif.}

Dear Don,

J is only being sold in The Piss Pot and The Hoof and Mouth, both Grant Avenue non-bookstores that don’t charge anything for handling it. We only print 300 copies and they sell out soon. At two bits why wouldn’t they?

I keep ten copies for my own—one of which I’d always send you. For extras tell people to send me a dollar and I’ll send them a copy if I like their letter. 50¢ west of the Mississippi and east of Mount Diablo. It’s me being me. California is an independent state—but I’ll demonstrate that in art.

The second issue (out before you get this letter) may tell you more. New York contributors are not forbidden but quotaed.

Love,

Jack

“Jack Spicer Papers,” BANC MSS 71/135, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. Donald Merriam Allen (1912-2004) was one of Spicer’s most influential friends, the editor of Frank O’Hara’s Collected Poems, and the editor of The New American Poetry (1945-1960). Spicer edited J with the painter Fran Herndon. Steve Clay and Rodney Phillips call J “in many ways the most beautiful of all the mimeo magazines,” and its 8 issues sparked many successors in the Bay Area and beyond. Allen served as J’s New York distributor.

To Jess #2

{December 1959}

{214 Sunnyside St., Piedmont, Calif.}

Dear Jess,

Just a note to thank you for the lovely dinner (I wrote a poem after it—the only poem I wrote while I was at Stinson) and to ask you to hold the baseball picture for me. I didn’t realize I had forgotten it until after I got back. When Duncan returns from Washington perhaps he can bring it in when he next comes into the city.

And the collages. You know what pleasure they gave me.

Love

Jack

“Robert Duncan Collection,” PCMS-0110, The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York.

To M. Eileen Fitzgerald

January 18, 1961

{1650 California St. #35, San Francisco, Calif.}

38 Galpin St.

Naugatuck, Conn.

Dear Miss Fitzgerald,

The San Francisco Group was started back in 1947. Buck Shaw was their coach and Tony Morabito was their owner. That, of course, was in the All America Conference.

Lately we have not been winning games although this year, due to our Shotgun Formation (really a variation of the Short Punt) we tied the Detroit Lions for second place in the Western League.

I joined the group in 1952 and except for having been traded to the Yankees and the Patriots in the 1955 and 1956 season have played with them ever since.

I cannot imagine writing a thesis about us because there are too many of us.

Yours sincerely,

Jack Spicer

A transcription appears in Robin Blaser’s typescript of letters in “Jack Spicer Papers,” BANC MSS 2004/209, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, with the note that the original is held by Jonathan Greene. M. Eileen Fitzgerald (1936–2019) wanted Spicer’s cooperation in her research for her master’s thesis, “The Beat Generation and the San Francisco Renaissance” (Southern Connecticut State University, 1963). What she got was Spicer’s willful misreading of his career as a poet as if he had been an athlete. Fitzgerald’s thesis did not offer much attention to Spicer, but it was one of the first scholarly works to have a substantial section on Duncan (along with sections on Denise Levertov and Brother Antoninus, representing the San Francisco Renaissance, and on Ginsberg, Kerouac, and John Clellon Holmes representing the Beat Generation). Spicer might have found common cause with Fitzgerald’s argument that “the Beat Generation and the San Francisco Renaissance are two separate and distinct groups. The first is a social protest and the second is a literary movement. Further . . . the poets of the San Francisco Renaissance have suffered from their identification with the social movement known as the Beat Generation.” Fitzgerald went on to a long career as a teacher and a school social worker. The San Francisco 49ers indeed were coached by Buck Shaw and owned by Tony Morabito when they first started playing in the All America (Football) Conference in 1946. Spicer came to live in San Francisco in 1952 after spending two years in Minnesota, and his seasons with the Yankees and the Patriots match up with the years he spent in New York and Boston. But the Yankees of course are not a football team and the Boston Patriots only began play in 1960, shortly before Spicer wrote this letter.

To Ariel Parkinson

{Spring 1962}

{1650 California St. #35, San Francisco, Calif.}

Dear Ariel,

Naturally I can’t thank you enough for the picture. The figures of the bull and the boy start emerging in the morning sun (opposite where the picture hangs) and start fading into jasmine in late afternoon. Beautiful.

That Gawain poem your show inspired has become a part of a long Holy Grail poem which I am about half through (27 poems in 4 books already). I intend to give you the original manuscript of it when it finished.

Love, Thankful Love

Jack

“Robert Duncan Collection,” PCMS-0110, The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. Painter Ariel Reynolds Parkinson (1925–2017) was part of the original Berkeley Renaissance scene in the 1940s, and was married to Thomas Parkinson. She recalls: “The drawing Jack mentions was made for ‘The Ballad of the Little Girl Who Invented the Universe’ [After Lorca, My Vocabulary Did This To Me, 109–10]. It had been in a solo exhibition of my paintings and drawings in the big east gallery of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1962. When the exhibition closed, I gave it to him” (“Letter to Lew Ellingham and Kevin Killian, June 25, 1991,” Kevin Killian and Dodie Bellamy Papers, Beinecke Library, Yale University). The poem Spicer mentions is the first section of “The Book of Gawain” (My Vocabulary Did This To Me, 331). That poem later became part of The Holy Grail (My Vocabulary Did This To Me, 329–58), which was begun in December 1961 or January 1962; “27 poems in 4 books” would indicate a date for this letter at Eastertime 1962. The book was completed by August 25, 1962.

To Fran Herndon

March 5, 1963

{1650 California St. #35, San Francisco, Calif.}

Dear Fran,

Thank you for writing the letter.

I think that over the last few months we have lost the elasticity of give-and-take that intimate friends, as we were, have and that we have both tried to pretend to ourselves and each other that the old rubber band was just as strong. I think that Robin is just a symptom for both of us.

Once we recognize that we are not the friends we were (at the moment I am almost George to you and you are almost Dora to me) we can establish a casual friendship which demands—and gives—less. Then, eyes open, we will probably become the intimate friends we once were.

Love,

Jack

Jack Spicer Papers, Bancroft MSS 99/94 c, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

To Robert Duncan #26

{1964}

Dear Duncan,

George, of course, did not deliver the message to you that he promised to deliver. The gist of it was this:

I have been identified through the Beach with the position that bars ought to pay poets adequate sums of money—cash not percentages. I have already persuaded several poets not to read at places (including Paul’s) where they would be paid too little. When Paul asked me to read on the Fall series for less than $25.00, I refused and told him you would refuse too. When I told you about this, you agreed and said you wouldn’t read for less than $25.00. I spread this story around and I think it had a good effect in stiffening other poets. When Paul put up a sign advertising you anyway, I asked you again and again and you said you wouldn’t read for less than $25.00. This again I told everybody. Your reason for changing your mind after this—cocking the snoot at Poetry Center—I quite sympathize with. I certainly was (and am) not angry—merely placed in an impossible position.

My pride, god knows, is pretty demanding, but I don’t think that pride alone would make me miss a reading that I would rather hear than any other and risk offending a person whose friendship (personal and poetic) is just about the most valuable one I have. It is a matter of stance—a better and more accurate word than principle—and in the case I have chosen to let it override both prudence and affection.

I will apologize a thousand times if necessary to obtain forgiveness for this, but I’m afraid that if the circumstances come up again I would have to act the same way.

Sorry to sound like Emile Zola. Viewed another way this is merely a tempest in a pisspot, I know. But it’s my pisspot.

Would you show this letter to Jess too?

Love

Jack

“Robert Duncan Collection,” PCMS-0110, The Poetry Collection of the University Libraries, University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. Spicer refers to George Stanley in the opening of the letter. “Paul’s” refers to the Buzz gallery, which Paul Alexander organized alongside several other artists. A number of poets read at Buzz including Jamie McInnis, Harold Dull, Joanne Kyger, and Stan Persky. Richard Brautigan attracted a large crowd when he read, over the course of two evenings, from In Watermelon Sugar, and LeRoi Jones likewise drew standing room only when he read at Buzz protected by bodyguards. But Spicer never read there, nor did Duncan; perhaps this letter explains why. See Paul Alexander, “Buzz Gallery,” Big Bridge (2003).

Lead Image: “Jack Spicer Papers,” BANC MSS 71/135, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

For information on Small Press Traffic's Fall 2025 Symposium (September 19-21), visit this link: Poetry as Magic: Celebrating the Fran Herndon & Jack Spicer Centennials.